Glad I didn’t use this Pearls Before Swine (AMS) when it appeared Sunday, because there has been an explosion of conversations about art and ethics in the days since.

Not, mind you, that this is the first time the issue of purchasing vs downloading music has come up. Doonesbury devoted a week to the topic back in 2002, of which these are a few samples:

It’s grimly amusing that Alex points a finger at “giant corporations and greedy musicians,” because the “greedy musicians” have taken a major beating over the intervening two decades, thanks to giant corporations like Spotify and YouTube and others, who found ways to profit by making music available basically for free.

Or at least in a way that nearly cut out the musicians entirely.

Musicians who used to get a cut of album sales are now getting checks for pennies as their compensation for being popular in on-line venues, and that doesn’t really change whether their music is actually being downloaded or just streamed.

I’m as guilty as any other old duffers in complaining that we used to pay $3.50 to get into a concert, but it’s not just the lasers and fireworks and blow-up characters who have made modern live shows so expensive: It’s also that concerts are about the only chance musicians have to make a living.

Rhymes with Orange (KFS) can be forgiven for the implication that buskers ever made ends meet, but Price and Piccolo are right that even CD sales are a vestige of the past.

I have a couple of boxes of CDs stashed under my bed, in part because I’m one of those strait-laced old men who buys music but in larger part because paying to download an album makes me nervous that, at some point, the Major Corporation will decide to make it disappear. Or my hard drive will fall apart. Or the cloud will dissipate.

So more of a belt-and-suspenders move than a sign of high ethics.

Further disclosure: Next to those boxes of CDs under the bed there is a box or two of self-published books. I sold enough to make back the cost of printing them, but they’ve never generated any actual income. Many musicians and writers can tell a similar tale, except maybe for the part about having earned back the original investment.

Still, while changes in the newspaper industry jerked my retirement plans from under my feet, I can scrape by on Social Security and whatever dribs and drabs wander in unexpected. I save my fear and pity for younger creative types who are still trying to figure out a world that is falling apart around their heads.

There has always been a lot of flailing for artists as they find their voices. When I was in my 20s, I was sure people would want to read about my college experience and now it seems we’ve got a generation of young cartoonists who think everyone wants to know what they went through in coming out.

Nobody does, but what you learn in the process can be harnessed into telling stories people do want to read, assuming you can feed yourself in the meantime.

Lord, at least I didn’t have Artificial Intelligence offering free material to people who might otherwise have paid me for a little side work.

David Blumenstein has created a long, fascinating and insightful look at the impact of AI on freelance artists, which is being praised by his fellow creators and deserves to be read not only by comics fans but by people in public relations and advertising and other places where an occasional commercial assignment can keep a starving artist from literally starving.

He talked to several fellow artists in putting it together, and treads a worthwhile line between “woe is me” and throwing cheerful fairy dust in your eyes.

It’s never been easy, and now it’s getting harder.

I wish I could argue with that, but I can’t.

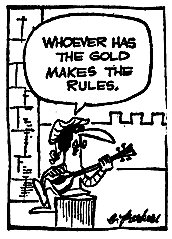

Jen Sorensen asks an inviting question, but I strongly suspect she knows the answer, which is that, as they say, freedom of the press belongs to the person who owns one.

Or, to quote Brant Parker and Johnny Hart:

There was a time not so long ago when small voices could be heard, at least by each other, through an underground press that was first undermined by Rolling Stone and then gobbled up by the aforementioned giant corporations.

For awhile, it seemed that the Internet would spawn a network of samizdat offering small discordant voices, but most of them fall apart and the ones which do gain a following are bought out and turned corporate, which appears to have become the hallmark of success.

At least in most places.

I said the other day that American cartoonists are too polite, that “political cartoons in those other countries seem to have some fearsome and enviable edge.”

There is, at this very moment, quite an example of that happening in Australia.

The Walkleys, a premiere annual competition has not only added a major fossil-fuel sponsor but is reportedly setting up award categories such that no greenwashing petroleum overlord will be offended by the winners.

Constant Readers will find many of the Walkleys’ most prominent critics to be people who are featured here regularly. And, bless their hearts, they aren’t simply criticizing.

Some of the most prominent cartoonists in the country are standing up and walking away:

If that seems like a Who’s Who of Aussie cartoonists you’ve regularly seen here, it’s because it’s a Who’s Who of Aussie cartoonists regularly seen in their own country.

Point being that it doesn’t really matter how this boycott impacts the Walkleys themselves, or the oil company that has joined their sponsor list.

The point is that these cartoonists, none of whom have ever shrunk from raising hell within their work, have stepped up to raise hell on a wider level and to join their voices in protest against those who ignore the growing climate crisis.

I don’t expect it to be a momentary fit of righteousness, either. Rather, commentators who have never shrunk from the battle are taking off their gloves and stepping up their efforts.

First Dog has put aside both color and sarcastic humor to make the point clearly:

This battle matters, and we’re not winning. Whose fault is that?

Dear Mike, WOW! You really pushed a lot of serious sensitive buttons, here. A couple of decades ago, our art organization withdrew almost all our artwork, books and multimedia works from our website as two evil behemoths (start with A and G) began stealing entire libraries of copyrighted works and making money from stolen copyrighted media. As you point out, it’s gotten worse.

I’m not advocating for or against, but Doones made the same mistake a lot of people have made.

‘Stealing”: depriving someone of something specific. “I stole your pencil.”

File sharing: I made an exact duplicate -down to the bite-marks- of your pencil.

It is illegal but it’s not exactly stealing. If so, you would be stealing for every song on the radio you heard. You would be stealing the scent at the bakery.

The whole point of this is we need to find a better word than stealing.

(fake email address to stay anon.)

RandomTroll

The more common term is “pirating”, but even that isn’t necessarily accurate.

But honestly, it’s weird that we still get bent out of shape over things that can reproduced with 100% accuracy. It’s not like anyone can make a perfect forgery of the ‘Mona Lisa’, but when it comes to digital works that can literally be copy/pasted, what exactly then is being stolen?

If musicians and artists create their work with the intention that nobody pay them, then of course it’s not stealing to not pay them. Beyond that, the Social Contract does not include a clause that says whatever you can get away with is perfectly all right. That includes both taking art that was created with compensation in mind and kissing soccer players on the mouth without their consent.

What’s being stolen is what’s known as ‘intellectual property’.

SOMEONE worked hard to create that song/performance/cartoon/painting/animation/software-application, and that SOMEONE deserves to be PAID for their efforts, which can only happen when people BUY that song/performance/cartoon/painting/animation/software-application rather than taking it without paying for it. Taking things of value without PAYING for them is….survey says: STEALING!

Unless we want to enter into Roddenberry’s money-less 23rd century economy where everyone’s needs are met, and the only competition is for esteem. Which doesn’t seem all that likely, given human history so far.

Specifically, radio stations pay for the music they play, which they then distribute to you. You’re not taking anything for which the musician has not been compensated. (The same is true of recorded music playing in a bar, assuming they’ve paid their ASCAP licensing. If not, then they are the thieves, not you.)

The scent in the bakery is reminiscent of an old Sufi story of the wise man passing through a bazaar in which a cook was demanding payment from a beggar for having inhaled steam coming from his stew pot. The wise man takes out his purse, shakes it, and says, “The sound of money in return for the smell of food.” The point of the joke being that there is nothing in Social Contract requiring payment in the case.

I absolutely agree piracy is not the same as theft. However, it is still a crime that deprives the IP owner of a nebulous amount of property, so I don’t think Doonesbury is too far off the mark here. Piracy doesn’t cause as much financial damage to the owner as theft which deprives them directly of property, but it incurs monetary an well as non-monetary costs. It isn’t “victimless”, but in some cases it’s similar in effect to shoplifting items with large markups (like soda) so we can pretend it is. So, even though calling piracy “theft” is inaccurate, that is rarely the appropriate argument or takeaway whenever this issue pops up.

Ironically, the fact that piracy isn’t theft is what makes it such a tricky crime to handle. How do you know how much money you’re truly losing when your work is copied without your knowledge? Many people who copy works would choose not to (or cannot afford to) purchase them. I feel the mane reason “theft” is a bad label for piracy is that corporations and powerful individuals have used it to justify outrageous claims of damages, such as charging a pirate full retail price for every album copy made (even more outrageous, given that this was initially happening at the same time as the industry was illegally price fixing to cost consumers billions USD).

But again: if you’re an artist, what is the actual cost of having your IP used against your will? It may include money, reputation, emotional trauma, or even becoming part and parcel to another crime. Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor wasn’t happy upon learning that his music was used to torture people held in Guantanamo, but there isn’t much of a legal amelioration available when a work is used in private. In the commoditification of everything (as both our legal system and capitalism do by necessity), how do you put a price on unfair use of IP when it is so widespread and much of the damage is often highly abstract?

My larger point here is that, while “theft” is misleading, it’s far more common to undersell the problem raised by piracy than to oversell it. I think this happens because people who aren’t involved in art generally imagine IP owners to be major corporations and (at least in the US) limited government regulation often means corps are free to behave in a villainous manner, so we can excuse it as a check on corruption in the entertainment industries. But the people most severely damaged by piracy will always be independent artists who cannot support themselves well (or at all) on artwork (or software, poetry, etc.) alone, who nonetheless have their IP directly copied and used without compensation, notification, or attribution. Ironically enough, these crimes are often committed by the same corporate entities who lead the charge against piracy, and they don’t care who gets hurt as long as their violations against small-time content creators doesn’t go viral (and often not even then).

This abuse was rampant long before GAI art became widely available, but GAI is taking it to another level. Developers used the artwork, heart, and creativity of millions of different artists without attribution or compensation to build those fancy GAI models. This may be fine for most conversational text on social media is cases where it is clearly not considered protected IP by the people posting their thoughts in public, but it is not okay for pictures, text from books, and other sources of creative IP. The only reason we tolerate the largest copyright violation in human history is because: 1) we all want to use it, 2) the victims have no accessible recourse to be compensated for what should clearly be illegal activity, and 3) the victims in almost all cases lack a substantial platform to place them above the fold on a national newspaper.

I don’t think this will change. People like GAI enough to excuse the crime. It’s like charity for starving children on the other side of the world: deep down we know it’s unethical not to donate financial support that literally saves lives and instead spend that money on luxuries, but we don’t care because the human brain is incredible at blocking out inconvenient facts and logical inconsistencies when it allows us to falsely excise the guilt from our many pleasures.

tl;Dr version: you’re right, but the “theft” label isn’t the problem we need to dialogue on.

So..(sorry) what were the self-published books, if I may ask?

A pair of newspaper serial stories, historical fiction that had originally run in the papers, one set in the War of 1812 and one in Prohibition. Samples here — https://www.weeklystorybook.com/