A friend emailed last night, wishing me luck in sorting through the inevitable flood of political cartoons that were already coming, inspired by the Nashville murders.

I responded “The real problem is people posting their old cartoons. I can’t tell the ones I’ve seen from the ones I only feel like I’ve seen.”

I particularly like Marc Murphy’s old cartoon, one from about a decade ago, because it feels so naive, today, to imagine that our forgetting was the result of the NRA’s efforts.

If he were creating it today, I’d suggest he not label the wave.

For all the efforts the gun lobby has made to negate the horror, our own ability to turn away, our own unwillingness to look horror in the eye, has proven sufficient.

Congress needs their money, but we don’t need their help to forget.

And Nick Anderson’s cartoon from 2017 could use a bit of editing, not that “It can’t happen here,” because we all know it can, but, rather, “It won’t happen here,” because we live in a state of denial, the laugh in this case being that, without pausing to count back, I have no idea which mass shooting he was commenting upon.

Our attitude reminds me of a conversation I had in 1983 with Tomas Cardinal O’Fiaich, during the Troubles in the North of Ireland, in which he told me

One thing that strikes me is that the Catholics of the South of Ireland, the southern part of my own diocese even, they want to distance themselves from the violence of the North. They’re inclined to say ‘God, keep it up there, as long as it stays away from us, we’re OK.’ There’s a certain attitude that I find a little bit unChristian in certain areas of the South.

It’s a terrible situation; the sadness and suffering that so many families in the North — Protestant and Catholic alike — have come through in recent years, and I mean, it’s not a thousand miles away, it’s not in Afghanistan or Iran or Iraq. We shouldn’t distance ourselves from any suffering, but at least it should be easier to distance ourselves from those than from something in Ireland. Yet they do try, even from something which I think Christian charity demands that we try to be helpful with.

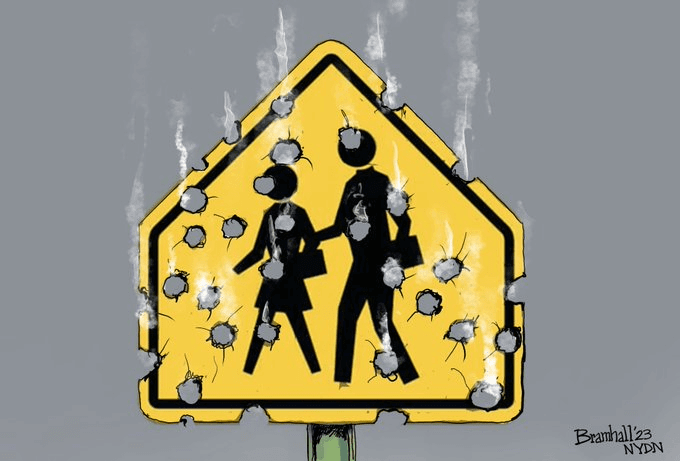

Still, God forgive us, when I saw Bill Bramhall’s commentary about the current killings, my response was that, while I like the cartoon, it doesn’t matter because we don’t care.

We simply don’t care.

The streets of Tel Aviv have been packed with people who care, and who have thereby succeeded, at least it appears at the moment, in turning around a government plan that seemed certain to move forward.

While Paris, too, has been thronged with those who cared about the government’s attempt to alter their retirement legislation.

As for America? Where are our crowds?

Ah, well, never mind. They’re not actually our children, after all. Just so long as it happens over there. And over there. And, again, over there.

Not here.

As long as it’s there, and not here, we can handle it.

We need an Emmett Till Moment.

As those with memories recall, or those who have seen the recent movie know, the abduction and murder of Emmett Till might have disappeared into the ongoing racist morass of lynchings and murders, had not his mother, with the cooperation of Jet Magazine, put her dead boy’s beaten, tortured face in front of America.

The resulting horror and outrage lit a spark under the Civil Rights Movement so that not only his murder, but the other murders of that dark era were no longer abstractions and reports, discreetly and politely muted so as not to disturb.

Coincidental with the Nashville killings, the Washington Post has published a special report on what bullets from an assault-style rifle do to a child’s body, (no paywall) but, even with the permission of two families of slaughtered children, they failed to come up to Mamie Till’s courageous, shocking level.

They marked their presentation with warnings and cautions and disclaimers, but then buried the unpleasant truth in illustrations and models, reducing it to a report on what bullets from an AR-15 can do to a dressmaker’s dummy.

It contains no more shock and horror than those old TV ads showing how much faster the little B’s of Bufferin get into your bloodstream than the little A’s of plain aspirin.

If you want to bring about change, if you want to make people care, you need to grab them by the lapels and slam them up against the wall, hard, and make them look, make them see.

If it upsets them, well, wasn’t that your point? And if that wasn’t your point, what the hell was?

The counter argument is that, if we start showing dead bodies all the time, they’ll lose their impact, but that’s a foolish argument.

We never saw photographs of Viola Liuzo or the three young men buried in the dam site or of Medgar Evers. It was sufficient to have rocked America out of our ignorance by showing us Emmett Till.

As someone who has trailed first responders for a living, I assure you that there’s no worry about it losing its impact. It won’t. It doesn’t. And if it does, you’ve no heart to be touched in the first place.

In the early 80’s, I spent three days in a pediatric critical care unit. One of the emergencies was a one-year-old who had crashed following delicate but relatively normal heart surgery. They had the poor little fellow all but disassembled as they systematically searched for the source of toxins flooding his body, but it was no go.

I should have been horrified, but we were in the moment, the adrenalin was pumping, everyone was on task and there was no time for sensitivity. I even stepped out into the corridor with the surgeon and the hospital chaplain to break the hearts of his parents.

All in a day’s work? Hardly.

As the crisis ended and the adrenalin drained, I saw the surgeon slumped on a stool, defeated and deflated, while the nurses cleaned up the table, a few of them blotting a tear as they did so.

This was back when female doctors were still rare, but there was one on staff, a brilliant crackerjack of a traumatist, and the nurses — all women — told me later, “We like working with her. She cries, and it gives us permission to cry.”

If we’re going to reverse this thing, we’re all going to need permission to cry.

Futility, by Wilfred Owen. Killed at 25, a week before the Armistice, 1918

Mike,

I needed your reflections this AM. At times, and lately too many times, we are not a very intelligent species. I am struggling to understand how this can happen again, and again, and again … with no substantive changes. I have a 9 year old grandson. I grieve when I consider the world he is inheriting.

I had wondered if Nancy Pelosi was going to have an Emmit Till Mom’s moment and broadcast pictures of her husband’s battered face. Might it have turned down the temperature?

But do we have a trusted media site that would publish it with the reverence that it deserves? And be accessible to everyone? Remember, we all watched the insurrection live on TV and we appear to have moved on….

Well written Mike, well written