CSotD: The River of Bull

Skip to comments

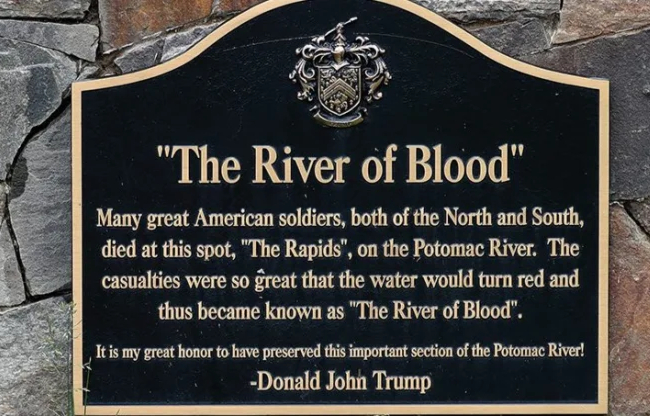

This historic plaque, celebrating a great Civil War battle, can be seen on the grounds of the Trump National Golf Club in Sterling, Virginia. There are eight “Trump National Golf Clubs,” but the River of Blood Battle didn’t really take place on any of them.

As the NYTimes reported a decade ago, it never happened at all.

“How would they know that?” Mr. Trump asked when told that local historians had called his plaque a fiction. “Were they there?”

Mr. Trump repeatedly said that “numerous historians” had told him that the golf club site was known as the River of Blood. But he said he did not remember their names.

But Donald Trump was just a blowhard real estate developer back then, and the fact that he had a penchant for ridiculous self-promotional nonsense was an amusing factor of an eccentric screwball.

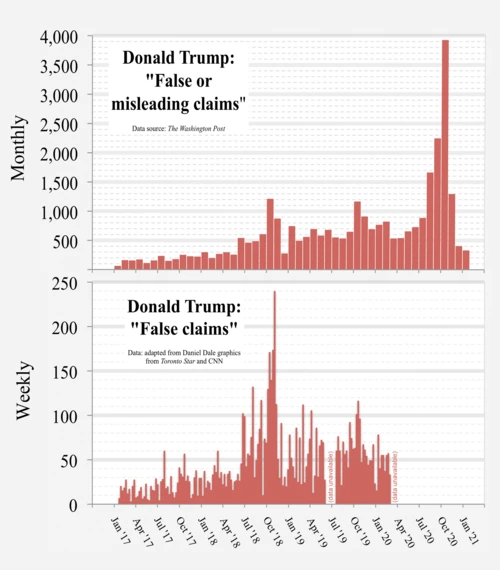

Until he became president in 2016, the media didn’t keep track of his lies, because they didn’t matter. We’ve all known the barroom braggart whose absurd collection of “facts” is a source of harmless amusement.

Things have changed since then, because when the President of the United States is a liar, it matters, and it particularly matters when, now that he’s in his second term, his “false or misleading claims” have become such an accepted part of his schtick that it seems nobody has been bothering to track them.

The current problem is that, not only does his bassackwards grasp of reality have the power to direct our economy and our national policies, but he has decided to use the power of his office to force universities to stop exploring certain topics and has announced plans to change exhibits in the Smithsonian to reflect his imaginary world instead of the real one.

Clay Jones has a passionate and entertaining essay on this toxic plan to miseducate the nation, but if you’d like a more wide-ranging and politically oriented discussion of the topic, here’s an essay by Joyce Vance about what it all portends for the nation.

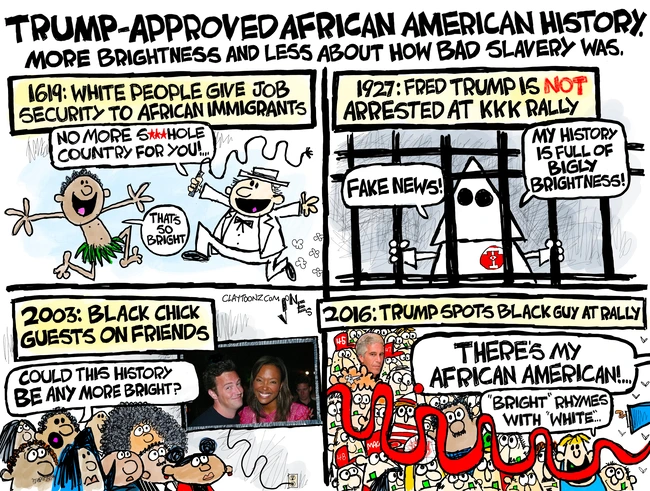

And Jones isn’t the only political cartoonists to mount the barricades over this outrage.

Juxtaposition of the Day

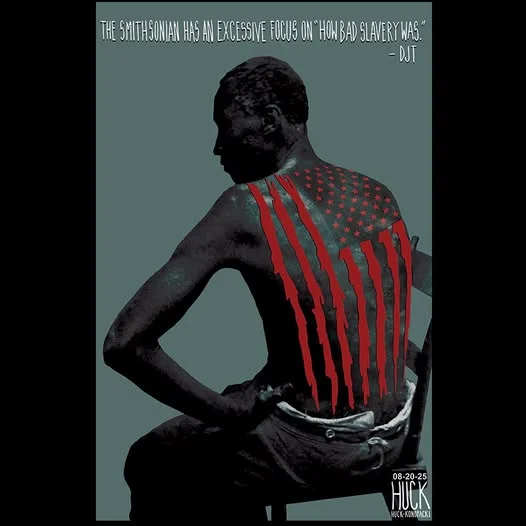

These are somewhat in descending order of mockery: Anderson, like Jones, proposes foolish ways to fix history, while Luckovich emphasizes the racism and white-supremacism at the center of Trump’s world view.

Huck, however, sees no humor, even mocking humor, in the situation and reminds us that, yes, there is fault to be placed, and that a stubborn refusal to deal honestly with our past intensifies and preserves the guilt that a more frank discussion could help resolve.

There is this to be said, not in defense of Trump’s demented view of the world but in the search for a better way to teach history:

The cure for bad history is not more bad history.

The Great Man Approach is deeply flawed. The notion that gifted giants arise spontaneously, as if from a vacuum, with fabulous ideas to change the world helps keep the peasants in awe of their betters, which is a toxic, counterproductive goal in a democracy.

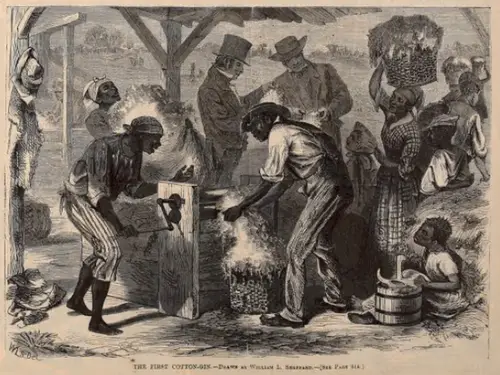

Napoleon, Julius Caesar and Donald Trump are only part of the Great Man Approach. Having kids memorize the names of George Westinghouse and Eli Whitney elevates innovations which were so close to development that, if Westinghouse and Whitney hadn’t been born, someone else would have invented the air brake and the cotton gin.

Whitney wasn’t the only person tinkering with ways to process cotton, and the significance of that improvement is what matters, not the person who came up with the most popular machine.

And the significance is that it boosted the cotton industry of the American South, and if you have to be told who was picking all that cotton, I can’t help you, but increased production meant an increased need for them, and, consequently, an increased resistance to calls for abolition.

The point is not to praise Whitney and have children learn his name, but, rather, to put the cotton gin into its perspective as an element that enhanced and preserved slavery.

How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes? — Samuel Johnson, 1775

Helluva question, Sam. It took us nearly a century to answer it, and it got worse before it got better.

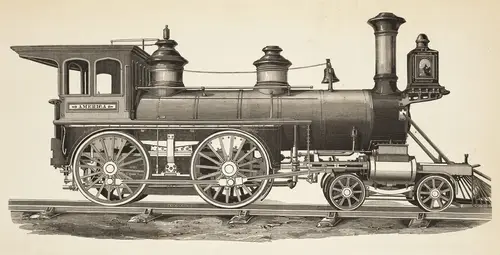

As for having kids learn George Westinghouse‘s name, the cure is not to have them learn that Elijah McCoy invented a way to lubricate steam engines, because there were other inventors working on those and related tasks.

It doesn’t matter that Westinghouse came up with the air brake or that McCoy came up with the lubrication system. Swapping one Great Man for another isn’t a cure. It’s just teaching more bad history.

What matters is that a variety of technical innovations made it possible for larger trains to carry larger loads over longer distances, which, in turn, opened up the American interior for the growth of cities, the centralization of industry and an expanding need both for labor and for agricultural production, which led to a major increase in our need for immigrants.

And an accepted need to remove the indigenous population from land needed for farms and mining.

It’s not that history is inevitable, but teaching Great Movements instead of teaching Great Men shifts the focus from a handful of individuals to the mass of people whose needs and wants drove our civilization, sometimes for better, sometimes not.

It should also force us to reconsider words like “we” and “our,” and to be sure of what they mean and who is included in them. Much of history depends on the answer.

Dear Leader said the other day that he is hoping that ending the war in Ukraine would enhance his chances in the afterlife:

I want to try and get to heaven if possible. I’m hearing I’m not doing well.

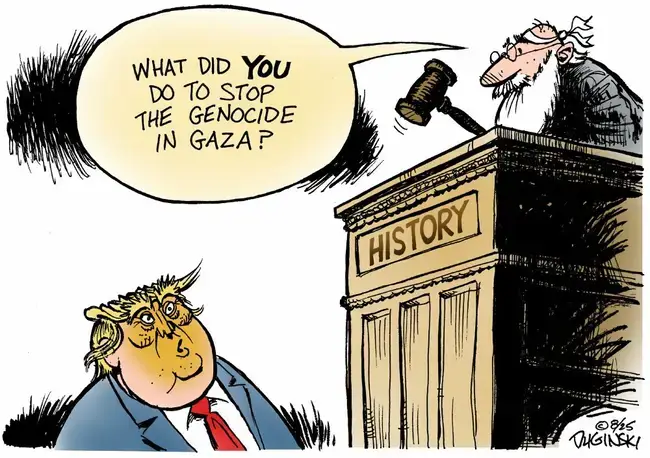

It’s quite a revelation, but Duginski takes an agnostic approach, suggesting that he will have to justify himself, if not to St. Peter, at least to history.

This is, however, the Great Man, rather than the Great Movement, Approach.

One day, we will all have to explain how we, as a people, allowed this to happen.

Comments 12

Comments are closed.